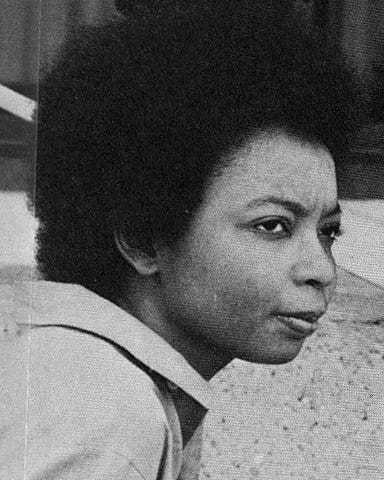

The Woman Who Vanished: The Myth of Gayl Jones

How one of America’s greatest writers slipped out of sight, and into legend.

It is said that Gayl Jones never entered a room, she simply appeared. One moment there was the hum of a literary gathering, the polite chatter of up-and-coming writers, and the next, her voice. Low, deliberate, edged with a quiet brilliance that made everyone else pause. Her words carried weight not because she sought the spotlight, but because she seemed indifferent to it. Jones was, in the literary world, a kind of apparition, so luminous on the page, so elusive in life.

And then, one day, she was gone. Not “retreated to a quiet country house” gone. Not “retired from public life to work in solitude” gone. But gone gone. She and her partner, Bob Higgins, had left, disappeared, escaped.

The word spread in whispers, circulating among the literati who had once marveled at her ferocity. Gayl Jones, whose debut novel, Corregidora, had detonated across the literary landscape, who had dared to tell stories no one else would touch, was now a fugitive. And with her went a love story, or maybe a tragedy, that no one could quite unravel.

Higgins was trouble. That much was known. Charismatic, erratic, always on the verge of brilliance or disaster. For years, he had orbited Jones, his volatility in sharp contrast to her tightly coiled precision. But it was this very tension, the union of the volatile and the controlled, that made them fascinating. Together, they seemed like characters out of a novel too daring to publish. And yet, whatever love bound them, whatever shared defiance kept them together, eventually became unsustainable. The whispers turned to headlines. Domestic incidents. Police reports. Then silence.

And what of Jones, the artist whose work peeled away every polite layer to expose the raw nerve beneath? Her writing had never flinched from the unspeakable. Corregidora traced generational trauma through the scalding lens of women who bore witness. Eva’s Man excavated the dark psychology of violence and survival. Jones’s fiction didn’t just break taboos, it annihilated them, reconstructing something unrelentingly honest in their place. But now, in the years when she lived on the run, her life began to echo those stories in ways that made her admirers uncomfortable. She had become too close to her characters, too enmeshed in the chaos she once wrote about.

Still, her absence did not diminish her myth. Among those who understood what her books had done, what they had given us, her name only grew more luminous in exile. She was mentioned in hushed tones in university hallways, her novels dissected at conferences by critics who never expected to see her in the audience. And yet, through it all, the question remained: What happens when a literary genius steps off the page and into a life as turbulent as her prose?

Jones’s story, like her work, resists resolution. There are no clean endings here, no tidy conclusions. What we have are her novels, jagged and brilliant, and the knowledge that somewhere, behind those words, was a woman who lived fiercely, who loved recklessly, who disappeared. A woman who might never step into the room again, but whose voice is still impossible to ignore.

Black Wonder is reader-supported—subscribe free or paid to keep the work alive.

Ms. Jones is a wonder. An enigma. Thank you for writing about this brilliant woman.